Shanghai—25 July, 2008:

Teacher, Teacher, Yi, Er, San, Si ...

"Teacher, teacher," my students said when they discovered that I did not know how to count in Chinese. The drilling began immediately: Yi, er, san, si, wu, liu, qi, ba, jiu, shi ...

I had come to China to teach English at a summer camp in Shanghai. I needed a break from Paris, I needed to get away from the "girls" in Pigalle. Shanghai seemed like a fine escape. There would be fewer language problems in Shanghai, as my knowledge of Chinese was extremely limited, unlike my knowledge of French, which always seemed to be getting me in trouble.

We had just come back from a field trip to Shen Shan (Shan means mountain) where it had been extremely hot. The kids had been dripping with perspiration, their clothing soaked. I had fanned many of them along the way up the mountain. One little girl, Shen Zhi Hui, aka "Caroline," I had fanned almost continuously, as it looked like she might pass out. Shen Shan may be a nice place to visit in Spring, Fall, or Winter, but in Summer it seemed more like a punishment for something you didn't do. I don't know whose idea this field trip was. The last part of it was fine, when we had our lunch in a grassy meadow half way down the mountain where there were hammocks, swings, gazebos, a concession stand, and even a maze for those who like to get lost and feel trapped. But the first part where we climbed to the top of the mountain to visit an old missionary church, then a tower with a telescope, was torturous. The sweat poured down the faces of the kids like little streams. "Kevin," Du Yu Ao, the most aggressive of the boys, was reduced to a pacifist puddle. At least the heat had some benefit.

At both the church and the telescope a tour guide gave a lecture but the kids drowned them out with the roar of their chatter, and no teacher made any attempt to quiet them. "When are we leaving, when are we leaving? I can't stand much more of this, how about you?" You could only see a pair of moving lips up front in the church or by the telescope in the tower, along with a tired gesture or two. But you heard nothing, which was probably a good thing. The missionaries did little to benefit China.

Above: The class visits Shen Shan on a very hot day.

Willa

and Caroline (glasses) are the girls with the recorders.

But back in the bus it was cool and nice with shaded windows and air conditioning. I had been waiting to get back in the bus most of the day and only longed slightly more for ice cream, an ever-favorite of all ages in Shanghai. An ice cream and a beer would have sent me straight to heaven, though not a missionary one..

But now that the secret was out—that teacher did not know the numbers—I now had a whole class of teachers trying to help me become "normal." Why they thought I should know Chinese numbers when I knew little other Chinese I do not know. "Cherry," or Chen Yi Shu, and Yu Hong, the only kid who did not have an adopted English name, both turned around in their high-back seats and drilled. Cherry, who was sitting in the window seat, drilled me between the gap in the two seats, while Yu Hong, who was in the aisle set, drilled me from over the top and around the side. They were two little friends who always sat together and had been less interested in teacher than the other girls and not as motivated. Truth to tell some parents send their kids to Summer school to have them out of the house, and this may have been the case for them. I don't know. But they had recently warmed up to me. They had decided that teacher was not the enemy.

It is a fine line between maintaining

control in a class of young children—these kids were all eight—and

being their friend. But maybe I was fortunate: I had a Chinese assistant

who, with a few sharply spoken words, was capable of restoring order instantly.

I don't know what he said but it must have been something like, "If

you don't behave I'm going to grind you up in Old Mao Ming's meat grinder,

bake you in dumplings, and feed them to the fish in the Huangpu River.

Do you want to so disgrace your parents?" The boys went bolt upright

whenever this, whatever it was, was said, while the girls politely quit

their private conversations. Thus I was spared being the bad guy most

of the time.

Of course the main trick to maintaining control of a young class is to be entertaining. You can do that by playing games but that would not be quite fair to your mission, mainly to teach them some English. So you try to make your lessons as game-like as possible, or at least talk on their level about things they know and care about. And don't bother with abstractions; they don't know what they are. If you are one who has been taught to believe that "be concrete" is the only way to teach or live, then eight-year olds are your perfect students. To them anything that is not concrete is just so much air vibrating your vocal cords.

It took me a few days to get this. I have mostly thought on the college level. One of my brightest students, "Linda," or Jiang Yu Chen, began sending me notes: "Teacher, we don't understand." Always with a smile of course. I learned to bring the lessons down to their level.

I rarely discussed grammar openly. But I did find a way to teach some grammar things without being too obvious about it:

"Maya, come up here," I said one day. Maya was only too happy to come up front with teacher.

Now "Maya," or Kuai Le, is standing in front of the class with me.

"Where are you?"

She looks at me wide-eyed with that I-don't-understand look.

"You're here," I say. Say it, "I'm here."

"I'm here," she says and seems satisfied.

Then I take here by the hand and we walk over to the other side of the room.

"Now where are we?" I ask.

She is not sure.

"We are 'here'," I say. "We can only be 'here' right now. We were 'there'," I say, "but now we are 'here'." And I point to where we were. Then I point to here and say "here" and point to where we were and say "there."

But that is enough abstraction, at least in the English language, for one lesson.

But now I'm in the hot spot getting drilled on numbers that in fact I once knew but forgot. Don't use something and after awhile the mind gets rid of it, or a least files it away in some remote archive.

And at last I'm getting them

down: Yi, er, san, si, wu, liu, qi, ba, jiu, shi ... Within a

few days they even become useful in the market. I am beyond Ni Hau,

and Zaijian but not armed with enough words to really get myself

into trouble.

Boys and Girls are not the same, duh! Yes, I should know that, but at this innocent age, aren't they roughly the same? No, not at all. "Hormones" may have not kicked in yet but something else certainly has. Let me repeat, if only for my own sake: Boys and girls are not the same!

So what's the difference, then? Well, for one things, girls are nice. Boys aren't. Girls like to work together, to learn new things, and be friends. They cooperate. Boys like to sabotage things; they like to cause trouble, fight, get in the way, and of course they pay no attention even if you are right in their face—unless, of course, you are the mean Chinese assistant shouting threats about drowning them in the river like rats.

Do I exaggerate? Sure, a little. But the differences are remarkable. Maybe there are super teachers who can hook eight-year-old boys into learning English. But I'd like to meet one. I'd love to know their secret, if there is one, which I doubt.

But to tell the truth, there are always exceptions and I did have one exception in my class. The exception was a young fellow by the name of "Frank," Shang Jia Hao. He got the usual bunch of "Needs Improvement" scores the first week, then some kind of transformation took place. I first noticed it when we had divided up into teams that were competing to name various forms of transformation. Frank was sitting, at that time, on what I privately called the "losers" side of the room, which contained most of the boys and some girls with limited attention. Frank's team, side B, was of course losing to side A, the good side. The good side had brainy Linda, wonderful Willa, good-natured Maya, artistic Caroline, and all-around good-kid Jessica.

I urged side B to name at least one more form of transportation before being defeated by side A. They looked like they could care less, like losing was their role in life. Then Frank's hand popped up.

"Metro light rail," said Frank in a soft but confident voice.

My assistant was about to threaten Frank with river drowning for making up words. Apparently my assistant didn't know what "metro light rail" was. I backed him off.

"Excellent," I told Frank. He was now hooked on the game and about five other forms of transportation that side A had not thought of came to him. I think it ended in a standoff. Every time side A thought of some new form of transpiration, Frank alone came up with another. I don't think the game produced a winner before we went into drawing forms of transportation, which is kind of the way I like it: No winners, no losers, just a lot of fun.

The next day Frank moved over to the other side of the room and was soon sitting next to Linda. He became highly participatory in all lessons but without being a showoff. He was focused and controlled and even, I thought, displayed humility. Linda was not always so humble. With a correct or clever answer, she gloated just a little at times. Thus I became one of Franks' admirers. He was rare for his age and I sensed potential in this kid. By the final week he got all exceptionals on his weekly report. It surprised me when I sat facing him and doing his report. There was simply no question on any of the categories. The transformation was simply astounding. Was he really a boy? Yes, at breaks he mostly went over and "horsed" around with the other boys, but I never had to run over and stop him from punching out some other kid; it didn't seem to be in his nature. Please, Lord, if you exist and are not of the missionary type, send us more boys like Frank. The world needs them.

On the other side there was Kevin, who, as I mentioned earlier, was aggressive. Kevin would be a good kid in an emergency. He would perform. Given an earthquake, I think he would risk his life to save people. In a war he would kill the enemy to save his country. But with the wrong influences, he could go the other way. What I'm thinking about is this: There was a concession stand at the park in the meadow at Shen Shan. They sold a variety of toys, including assault rifles and swords. Kevin bought an assault rifle immediately and spent much of the afternoon symbolically killing all the little girls in the park. If you witnessed this, you would know what is wrong with selling symbols of death and destruction to kids. It makes them think that killing is good.

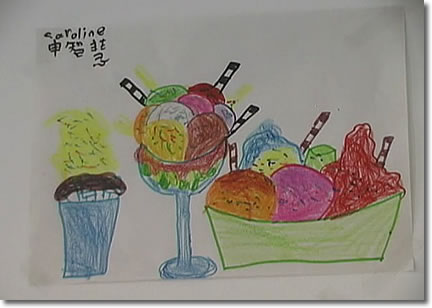

One of my favorite activities was getting out of the classroom. The excuse was observation. We would pick a place to go play the roles of reporter and artist. After we had made our observations we returned to the classroom, talked about what we had seen, wrote about it, and drew a picture of it. No one ever objected to this game, even though it was hot outside — sometimes about a 100 degrees—and the classroom was air-conditioned, cool, and comfortable. Such escapes were precious to all. Life was outside the classroom, and in the classroom we examined life. Let the other classes sit in their classrooms and miss all that was happening "over there", outside the window, "beyond," which was our here and now, at least for awhile.

Where did we go? We went down the school corridor on the second floor to where it opened up on a patio below. There we noted "stuff": trees, grass, birds, butterflies, a maintenance man, whatever we found. Then we went down to the patio and had a closer look. We got into the trees and the bushes and prowled around. We found the shells of snails, we looked at butterflies close up, noting the spots on their white wings and the dark tips, we found a flex-straw under leaves, we found a little pound by the side of the wall where a pipe was leaking, and someone spotted brown ants, ...

Other days we went to the football field that was lined with trees and hedges where we wandered in the shade and looked back at the school. We noted cars in the street outside and the red roofs of apartment buildings across the street. More butterflies showed up and landed in the garden spreading their wings. There were all of the white-butterfly-with-spots-and-tipped-wings family. But now we noticed that they were not quite so white as we thought; they were more of a beige or milky-white color. They were all of medium size, none large. Back in the cool classroom we wrote down what we saw and drew pictures. What fun! What strange pictures we tapped to the walls latter in the day: A puddle, some ants, and a straw.

Actually I should say this: Most drew pictures of what they saw. There was a boy who sat on the good side of the room in the back and was well behaved. He drew ships and boats. It didn't matter what the assignment was, he always drew a ship or boat that he picked out of book that he brought with him from home. I never corrected him for it, as that was his passion and he did good work. One day when we were doing an exercise on naming types of stores, combined with writing a sentence naming your favorite store and drawing it, I asked "Harry", or Wang Wei Xing, if he were drawing a shipyard where boats were sold. Yes, that is exactly what he was doing, he said. I admired the detail that he put into his drawings, almost all of them with pencil and without color. Unlike my other students, who used color lavishly, Harry was of the old, no-nonsense, black-and-white school.

Observation and memory can be strange at times. On both field trips—we made another to Shanghai Aquatic Park—when we came back and talked about them the next day, initially no one could remember anything at all. It was like they had not been there. Or if they had, it had been a bad experience that they did not wish to discuss in public. For the first five or ten minutes, no one could name any one thing they had seen. I was amazed. Then slowly they began to remember things. It may really have been that these were unpleasant experiences contrived by educators. The most memorable thing to me about the trip to the aquatic park was coming back and eating ice cream. Yes, they did remember that.

"Anyone see the scorpion fish?" I asked. No one remembered it. It was an exotic creature, spooky looking, and glowed in gold. But then it was in a tank higher than they are; they may have walked right by it without looking up.

"Anyone see the lion fish?" Nope, no one.

"Anyone go to the Shanghai Aquatic Park yesterday?" I asked. Most raised their hands but still not one had seen anything! What to make of this?

Okay, ten minutes later they were starting to remember things. It was coming back. Then we drew fish, and clearly they had been there despite themselves. Maybe they really had repressed some of what they saw due to an unpleasant experience: It was crowded at the indoor park and stuffy and the trip was really too long. One kid even got lost; I'm surprised more were not. (Yes, he was found but it took awhile.) I was exhausted by the end and I think they were too. That is why I think they all remembered the return to the cool classroom and the ice cream. That was the best part of the trip, though not officially a part of it.

"My brother is nice and mean," wrote Maya. Actually, I don't think Maya has a brother, due to China's one-child rule, so she may have given herself some leeway in constructing the sentence.

"Can a person be nice and mean at the same time?" I asked. Why not was the look I got from the class. Yes, I was going into the abstract and probably doomed to failure. Linda smiled like she understood the problem with this sentence but I did not pursue it. Hell, maybe Maya's imaginary brother really is nice at times, mean at other times, or sometimes combines the two.

We were doing a lesson on feeling or emotion words. I sensed some resistance but then they got into it. Later I was told by one of the Chinese instructors that emotions are best avoided ... But I didn't quite believe that. There was a lesson in the text supplied by the school, which I and the other teachers never in fact used, on including a compliment to the other person when introducing yourself. I didn't quite buy that either. But it did inspire me to introduce both positive and negative emotions.

"Okay," I said, "not everyone is nice, right?"

I had some agreement there.

"Some people are even not nice, bad, mean? Think of anyone?"

Well, we weren't naming names but I got a look of general agreement on this.

"Let's list the positive stuff on this side of the board and the bad stuff on the other," I said.

Right and left sides of the board quickly filled up.

"Okay, so write me a sentence that uses some of these words."

That is where "My brother is nice and mean" showed up. Fine. They were expressing themselves. Know that song that Billy Holiday sings so well? "My man, he don't love me, he treats me awful mean ... But when he starts into loving me ..." The world is full of contradictions, especially when it comes to emotions. We also made a made a list of words that were neither positive nor negative, a list of "middle" words that might go either way.

Maya was actually an interesting kid: She wanted a lot of attention and usually got it, at least for awhile. When I asked the class questions she would raise her hand just to have me come over. When I asked what the answer was, she gave me a blank look; she didn't know. I let he hang on me a lot; she seemed to need it.

One little boy in the beginning was a pain in the butt. I felt like killing him. I mentioned him to another teacher, Alix from the UK, who had been having a similar problem with a student. He told me something like this:

"I thought about it last night and I realized that this kid was starved for attention. I watch when his parents show up to pick him up, and they don't even look at him. I tried this today: I brought him up to the front of the classroom with me and had him work at the desk. He became an angel! You might try it."

I was skeptical. This kid was rotten. But I tried it anyway. It worked wonders. The kid sat and worked and helped pass out stars to the other students. Apparently what he needed was personal attention. I'm sure this does not work with all but it did with this kid. I don't remember clearly who this kid was but I think it may have been Frank. I did find with some of the others, like Cheery and Hong, who were initially marginal, that personal attention really did matter. Give kids personal attention, encourage them, and they stop ignoring you. Give them a chance and they give you a chance.

Above: A sweep of the class during an art session.

Suggested sentences

to go with the art are on the white board. The two students in the middle

are

Linda and Frank.

Linda? Linda made the class worth while. The private looks of comprehension and understanding, the amused look in her eyes, kept me going. She is what makes you say "my kids" when talking to other teachers about your class. They begin to feel like your own children after awhile. And then there was Willa, who was a runner up with Linda for keeping me going. She was smart like Linda but a very all-around kid and affectionate. If I had a special friend in class, it was Willa. I loved it the day before we went to Shen Shan when she asked where we were going, heard the answer—I think she had been there before—then slumped out of her chair down to the floor as if she had been shot. Pure drama; she was right back up in her seat. But she came. Brainy Linda didn't show. Who can blame here? She had been sick off and on with a stomach problem and fever and probably did not what to risk ending her life on a silly field trip.